Indigenous communities across Guyana—more than 200—should receive 15% of the money Guyana makes from selling its carbon credits.

And Toshaos, who are Indigenous leaders, seem intent on using the funds allocated to their communities to implement much-needed plans and programmes.

Karrau, a riverside community in Region Seven (Cuyuni-Mazaruni), needs income-generating ventures to help boost people’s livelihoods. A huge chunk of its GY$24 million (about US$114,000) will be used to expand logging and sawmilling.

“Logging is a major area for us.

“Most persons do logging but we want to convert the logs to lumber,” Karrau’s Toshao Shane Cornelius said, adding that logging is one of the community’s main economic activities.

Karrau has a population of over 500 people. Cornelius estimates that about 20 households are involved in logging. Sawmilling, however, would help the villagers earn more.

“With the sawmilling, the Village Council will be doing it as a business and we intend to buy logs from loggers hence maintaining the circular flow of income,” Toshao Cornelius explained.

The trees that will be used to help Karrau earn more are among Guyana’s forest resources, helping it earn these carbon credits in the first place.

Indigenous communities are regarded as the custodians of Guyana’s vast, intact forests. Many of these communities are found in forested areas and help authorities monitor activities, be it logging or mining, that impact the forests.

Deforestation in the country, over the past decade, has ranged between 0.02% to 0.06%; it is among the lowest rates in the world. And Karrau believes it will be able to continue aiding the sustainable management of Guyana’s forests even as it intensifies logging and sawmilling.

Toshao Cornelius believes the direct allocation of funds from the carbon credits deal is one that helps to reward Indigenous communities for their environmental stewardship.

“As Indigenous peoples, I think we are being rewarded for our stewardship.

“I await other companies to buy the remaining carbon credits so that we can continue bridging the gap that exists between the coast and the hinterland,” the Toshao said.

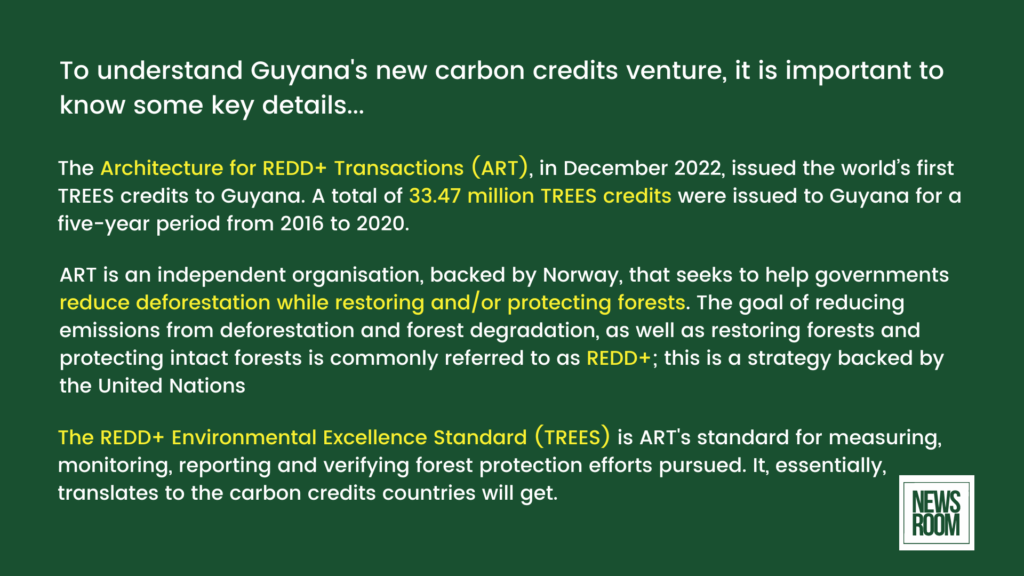

How exactly does this venture work, though?

Guyana’s first and only carbon credit deal so far, brokered after the country got special carbon credits issued to it last December, was executed with Hess Corporation, a US oil giant and one of the companies searching for and producing petroleum in the country’s nascent oil and gas sector.

A carbon credit, generally, is a kind of tradable permit or certificate that represents the removal of a certain amount of carbon dioxide from the environment. Since carbon dioxide is the principal greenhouse gas that harms the environment, it is tracked and traded like any other commodity.

Hess, an oil company, hopes these credits will help improve, or at least offset, its environmental actions. The oil industry is notorious for emitting harmful greenhouse gases.

By the end of 2030, Guyana should amass at least US$750 million from the deal inked with Hess. Of that sum, Indigenous communities, altogether, should receive at least US$112 million—that is, their 15% direct cut as stipulated by Guyana’s Low Carbon Development Strategy (LCDS).

Concerns about the carbon credit venture were, however, raised by at least one Indigenous rights organisation.

The Amerindian Peoples Association (APA), in a statement issued last December after the Hess deal was announced, questioned how the authorities arrived at the 15% revenue allocation figure, contending that there were not adequate consultations on this.

Guyana’s authorities maintained that enough consultations were done when the government was updating the LCDS, and earlier this year, Guyana received the first tranche of payments from Hess.

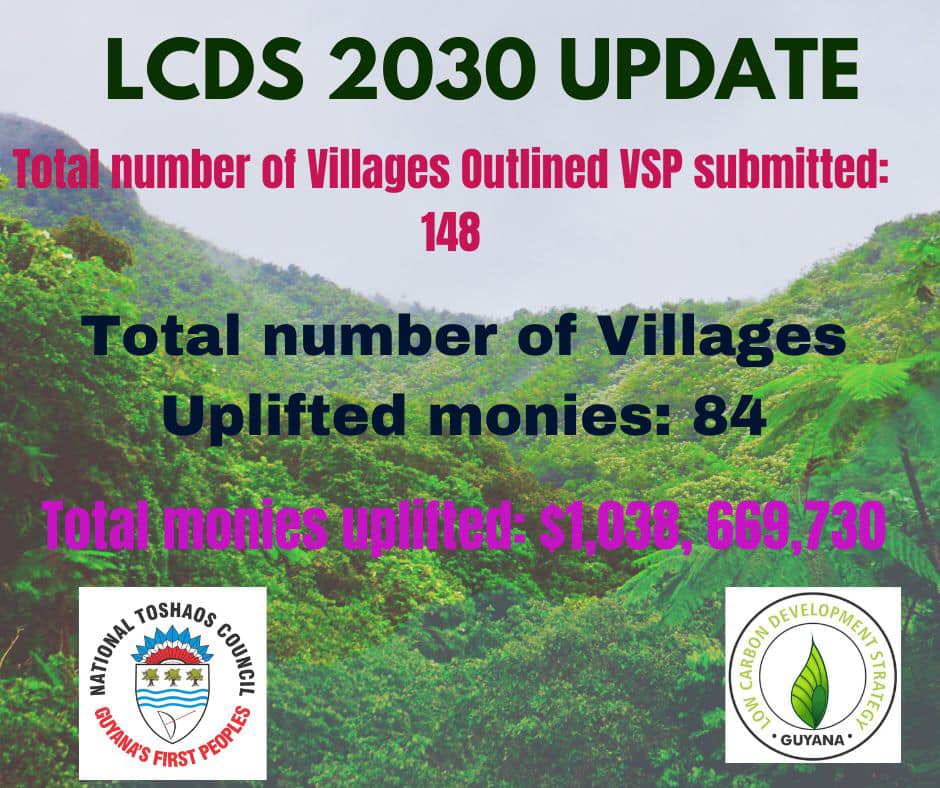

The process of disbursing funds to Indigenous communities then got underway.

In February, Guyana’s Vice President, Dr. Bharrat Jagdeo, said each community would get between GY$10 million (about US$47,000) and GY$35 million (about US$166,000).

Population size was one of the key determinants of the allocation. That helped determine how Karrau would get the GY$24 million sum.

But before the communities got the money, they were required to open a new bank account for their funds to be deposited into. Additionally, they had to create Village Development Plans that outline how the money will be spent. Ideally, those plans were created after in-village consultations.

Toshao Cornelius, for example, said Karrau’s projects were identified by villagers and included in the community’s development plan. The community also plans to purchase a boat and engine to help transport children and other residents, as well as a generator for electricity.

Communities elsewhere are pursuing similar initiatives

In the South Pakaraima area of Region Nine (Upper Takutu- Upper Essequibo), the Karasabai sub-district is set to receive GY$35.8 million (roughly US$170,000).

Regional Councillor for the subdistrict, Vania Albert, highlighted some plans several communities in the subdistrict have.

Rukumuta, for example, will upgrade the Corona Falls trail in an attempt to attract tourists there. Other infrastructural works, such as constructing community bridges, building a fuel depot, and expanding the village shop, will help the village cater to tourists.

Tigerpond, Albert shared, hopes to expand agriculture; a banana farm is in the works. Other projects in this community include purchasing sewing machines for the local women’s group and reforesting water cedar plants.

The community of Pai Pang hopes to invest in equipment that will help villagers process cassava grown there; the community will also spend on maintaining internal roads and purchasing solar-powered street lights.

Among the plans for Kokshebai, according to Albert, is to purchase pigs, sheep, and chickens so that the community can get into animal rearing on a larger scale. With these plans, Kokshebai will also invest in fencing the animal-rearing and farming areas.

And the story repeats itself in other communities. Toshaos, the Village councils, and the residents themselves are exploring how they can earn more while upgrading their communities’ environment.

Guyana’s Vice President, hours before announcing how the first tranche of funds would be divided among the indigenous communities, said the government hoped the communities would spend their allocations, at least in part, on income-generating ventures.

He, however, noted that the government did not want to dictate how the funds would be spent. Instead, he said community consultations were needed.

The Toshao of Bethany in Region Two (Pomeroon- Supenaam), Sonia Latchman, explained that the residents in her village identified six areas they wanted to focus on: health, education, nature and the environment, governance, livelihood development, and culture and tradition.

“Having come up with those projects, the village decided to look at the priority projects.

“These projects were passed by a village general meeting,” she said.

Bethany, like Karrau, got GY$24 million. Toshao Latchman said the community wants to boost poultry production, so it is investing in birds and developing the pens and stations needed. Bethany will also invest in a tractor to aid in ongoing farming and logging.

At a recent press conference, Vice President Jagdeo confirmed that the funds designated for Indigenous communities have been deposited into “over 240” bank accounts.

“Some have already started to draw down; I am aware that we are making progress in this regard,” he said.

This story was published by The News Room with the support of the Caribbean Climate Justice Journalism Fellowship, which is a joint venture between Climate Tracker and Open Society Foundations.