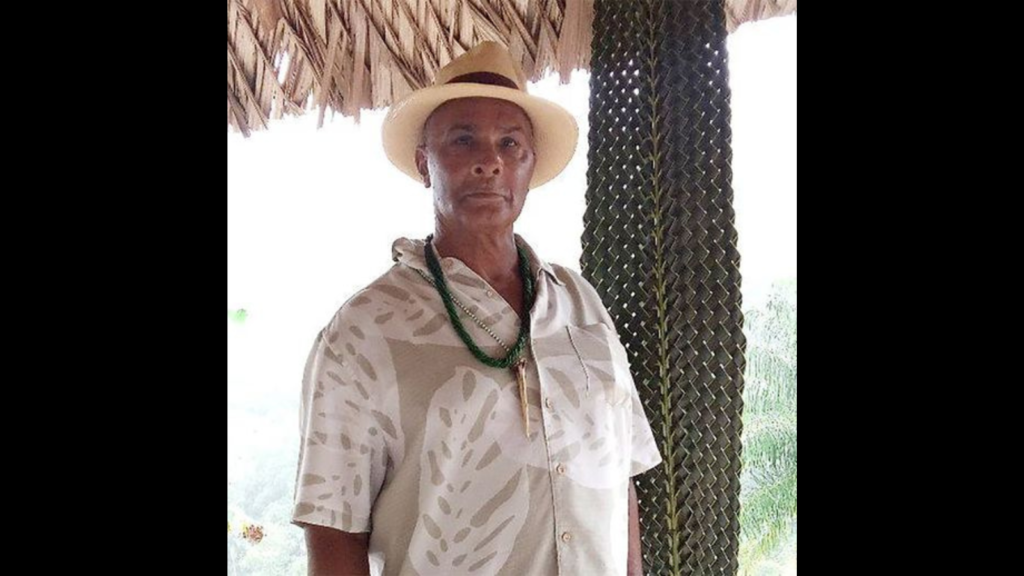

For decades, Cristo Adonis has turned to the land for healing. Known across Trinidad and Tobago for his knowledge of bush medicine, he has used indigenous plants to treat ailments long before conventional medicine became mainstream. But now, he finds himself fighting a new battle — to protect these plants from extinction.

A shaman, parang singer, hut builder, gardener, and hunter, Adonis is a central figure in the Santa Rosa First Peoples Community. His work preserving Amerindian traditions and advocating for Indigenous rights is well known. Today, however, the focus has shifted to the intersection of tradition and climate change.

Coastal Communities at Risk

First Peoples in T&T have long settled near rivers and coastal areas — a connection rooted in their traditions and dependence on natural resources. But now, rising sea levels are eating away at these communities.

Speaking with several Indigenous people across the islands, many cited the worsening impacts of climate change. Tobago’s Kalinago communities, in particular, are seeing firsthand the effects of coastal erosion, deforestation, quarrying, and uncontrolled human development.

The changes aren’t only physical. Agriculture – a key pillar of Indigenous life – is also under threat.

Farming Traditions Disrupted

Ricardo Bharath-Hernandez, Chief of the Santa Rosa First Peoples Community, said fluctuating weather patterns are severely impacting traditional farming. Droughts stunt crop growth, floods destroy fields, and unpredictable seasons throw off long-standing planting cycles.

“Increasing temperatures are affecting their agricultural habits,” he noted, emphasising how climate change is making it harder for First Peoples farmers to plan and survive.

Jinella De Ramos, who traces her ancestry to the Amerindians, shared similar concerns.

“Indigenous people have always been custodians and protectors of the rivers, forests, and wildlife. The volume of water we had long ago is not the same due to climate change, and the Indigenous people have always thrived near riverbanks. There is limited access to water and clean water in various areas where it was once in abundance,” she explained.

Plants in Peril

Adonis, an expert in native flora, fears for the survival of plants like Lozei Bwa, which once thrived in cool, damp environments but are now struggling as conditions dry up.

“If you take a plant like the Lozei Bwa, which thrives in more damp and cool places, and some of the areas where that plant would blossom are getting dry now. I’m already seeing the effects of what this dry season will do,” he said.

These days, Adonis must travel further to find the herbs he once collected nearby. In response, he’s started replanting endangered varieties to preserve them for future generations.

Health, Heritage and Survival

The threats don’t end with agriculture. Both De Ramos and Adonis highlighted the growing health risks for Indigenous communities, including heat stress and the spread of vector-borne diseases.

Bharath-Hernandez also warned about the erosion of traditional knowledge.

“Obviously ,climate change is going to have some impact on Indigenous people; whatever government policy or whatever they plan to do should involve us because, as you know, Indigenous people depend a lot on nature, which the climate will affect in more ways than one. Consultation is important,” he said.

De Ramos added that Indigenous voices have long been undervalued.

“The philosophy of the Indigenous peoples has not been taken into consideration very seriously in many instances. Their ideas and contributions can sometimes be viewed as irrelevant because of their humble lifestyle and the perception that they are not fit to be part of the conversation. Their knowledge of our ecosystems, sustainable practices, and healthy life choices can contribute to a better way of caring for our environment since us humans are part of it and affected by it.”

Toward Community Resilience

Kishan Kumarsingh, head of the Multilateral Environmental Agreements Unit at the Ministry of Planning and Development, acknowledged that building climate resilience must happen at the community level — and that includes Indigenous communities.

“This will require assessment of climate risks and implementing measures to minimise or eliminate these risks,” he explained.

Kumarsingh referenced the South Oropouche River Basin study, which aims to include local knowledge in shaping climate responses. He also highlighted the National Adaptation Plan, which covers sectors such as coastal resources, water, agriculture, and health — all of which are deeply relevant to First Peoples.

“Building climate resilience at the community level has been the focus of the Ministry of Planning and Development through the development of projects and policy utilising an ‘empowerment through ownership’ approach,” he said.

For Bharath-Hernandez, the solution lies in bridging the gap between traditional and modern knowledge systems.

“We see the Government is looking at more modernised forms of agriculture, and I think in the process, the Indigenous people should be included because they know the traditional ways. Because of the changing climate, Indigenous people have to fall into what is happening now.”

A Fight for Survival

As the climate crisis deepens, even the most rooted communities are being forced to adapt. For T&T’s First Peoples, the fight to protect their land, heritage, and knowledge is also a fight for survival.

—

This story was originally published by the Trinidad and Tobago Guardian, with the support of the Caribbean Climate Justice Journalism Fellowship, which is a joint venture between Climate Tracker Caribbean and Open Society Foundations.