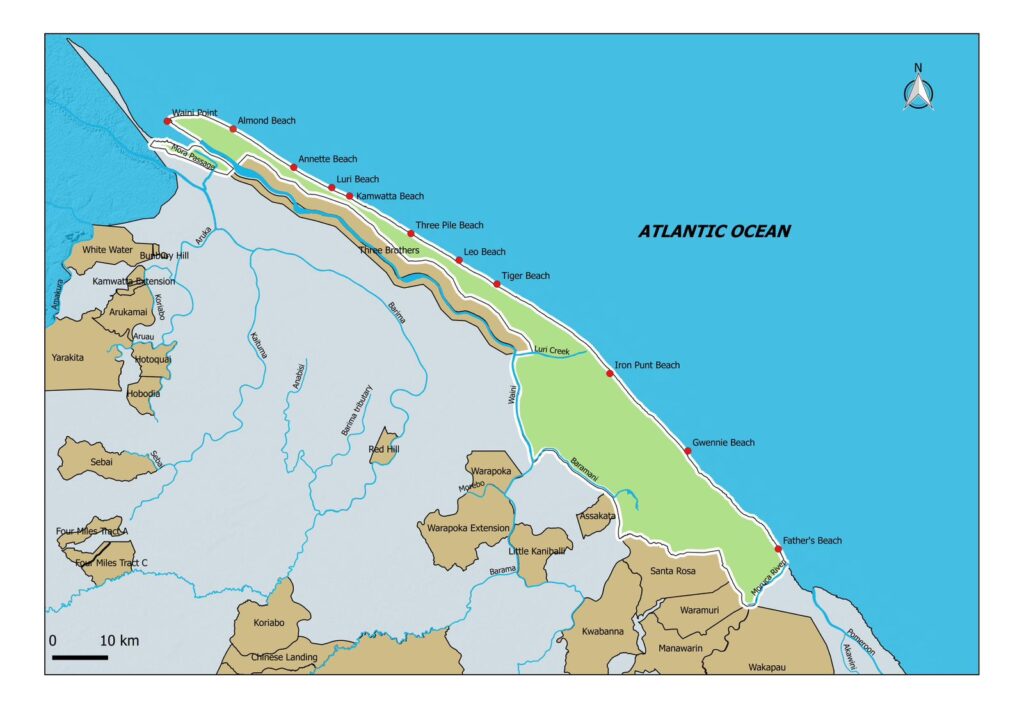

Almond Beach is an Indigenous community and one of 10 beaches found along the 75-mile-long Shell Beach Protected Area in Region One (Barima-Waini).

Every year, you can find four endangered species of sea turtles nesting there. Those turtles are the Leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea), Hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata), Olive Ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea), and Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas).

Conservation stakeholders, such as Guyana’s Protected Areas Commission (PAC) and residents of Almond Beach, are among those who help protect the turtles and their hatchlings during the annual nesting season, that is, from February to August.

Over the past few years, however, the coastline at Almond Beach and other parts of the Shell Beach area has been eroding at an increasingly fast rate. This poses challenges for the residents and the turtles that have grown accustomed to nesting there every year.

“Over the years, Almond Beach was one of the best places.

“People across the globe know about Almond Beach because of the sea turtle nesting,” Arnold Benjamin, the Almond Beach Community Development Council Chairman, told the News Room during a recent visit to Region One.

Benjamin, however, noted that the erosion has significantly affected life at Almond Beach. For example, the community no longer has the school that was constructed there in response to the growing population in the 1990s.

According to Benjamin, between 1991 and 1997, about 150 people lived on the beach. Because of the population growth, several facilities were constructed: a school, a church, and a ball field (a recreational area).

By 2005, the school was dismantled and moved further inland because the coastline had receded.

“It was really rapid,” Benjamin said.

He added, “It forced people to move. We lost about two miles (of land), farms (and) coconut trees.”

Over the next 10 years, the erosion continued, and the residents moved further inland. Eventually, Benjamin said they asked the government not to dismantle and reconstruct the school; it was just a “waste of money” and families started leaving the beach.

Benjamin is among those people who believe the residents are climate migrants because erosion, as a result of or worsened by climatic changes, forced them to migrate.

So what is causing the erosion?

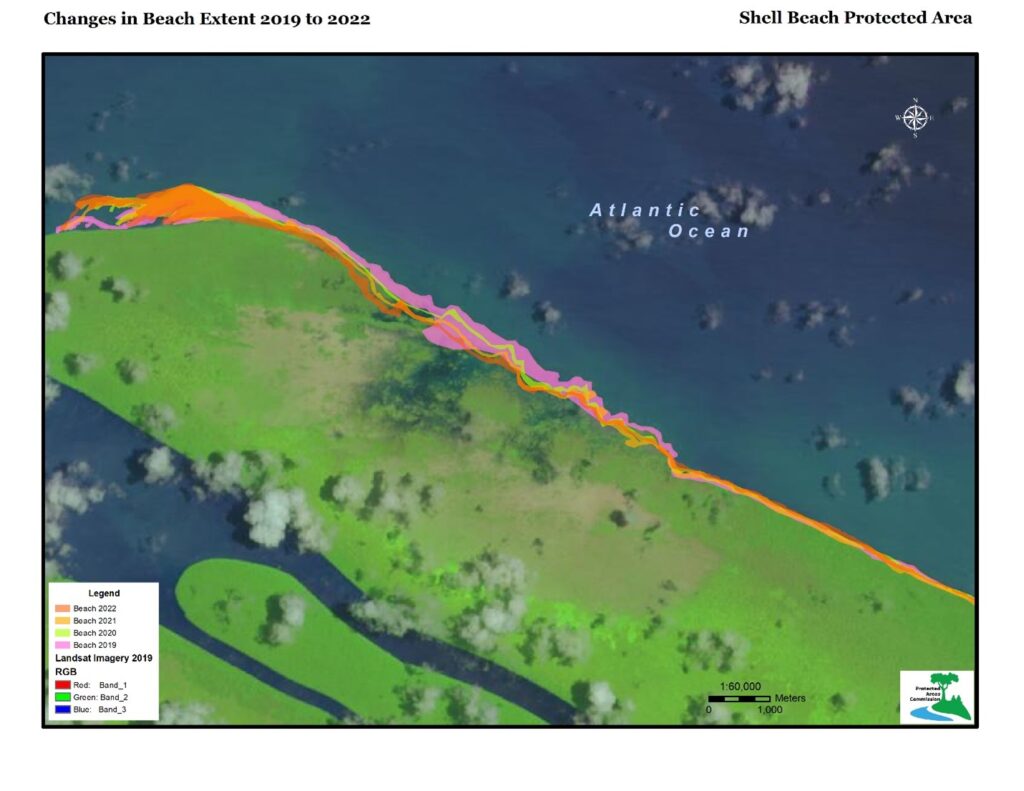

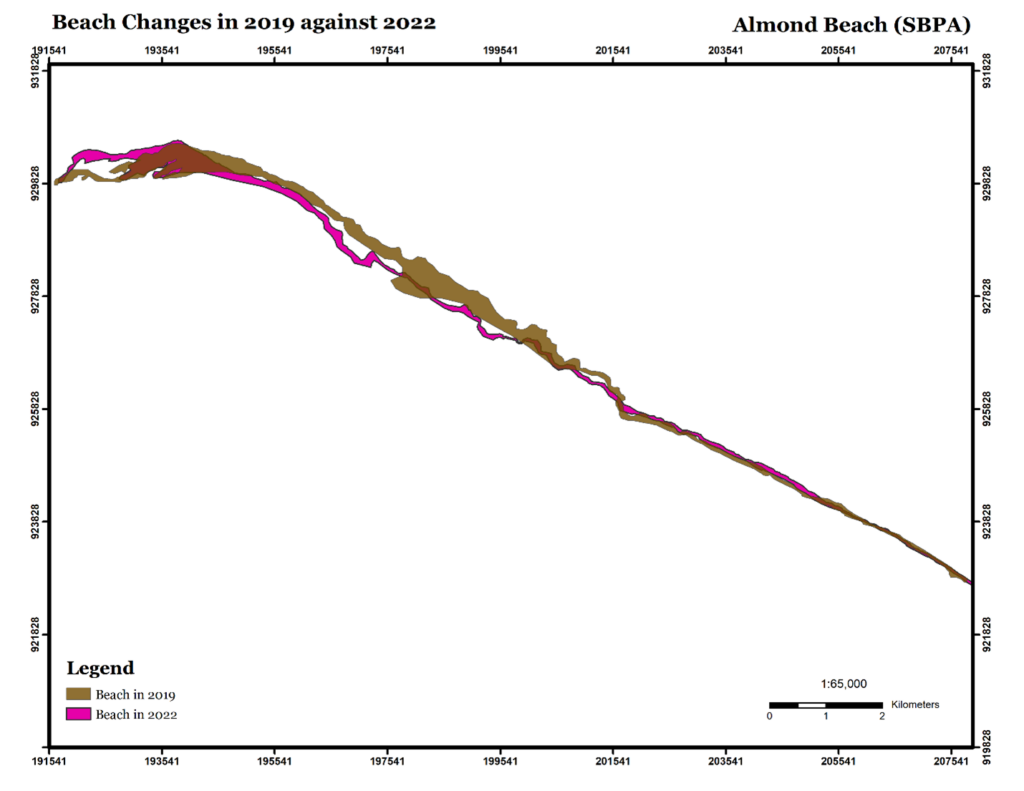

Based on data collected and analysed between 2019 and 2023, the PAC found that parts of the Shell Beach coastline have been washed away by the Atlantic Ocean.

The PAC is the body with oversight for Guyana’s protected areas, including the Shell Beach Area. The Commission also found that the Shell Beach coastline had a mass area of about 1.3 miles in 2019. In 2022, that was reduced to a mass area of about 0.7 miles.

The beach is eroding from the eastern end, while accretion, which is the dumping of the materials washed away, is happening at the western end.

The coastal changes are part of a seemingly natural 30-year cycle, but the PAC also noted, “These changes are believed to be a result of climatic changes which have resulted in stronger ocean currents and intense wave action.”

PAC’s data also revealed there were 70 people living there in 2014; at the beginning of 2023, only three families were living there.

The Thornhills are among those who remained – at least until now.

Residents help save the turtles

Leonard Thornhill moved from Moruca, a Region One community found more inland, to Almond Beach about 35 years ago.

“Over the years, it [the erosion] wasn’t affecting us like how it is during this time.

“Back in the years, the erosion was, like, slow but from like two years back we experienced it moving very fast,” Thornhill said as he sat on the beach recalling the coastal changes he has been observing.

Thornhill said life as he knows it is on Almond Beach so moving would be very difficult.

Seine nets are scattered around his wooden house; his farms are located further inland. These are indications of how he makes a living on the beach.

“Most of my children, they born and grow on Shell Beach so it’s kinda hard to take them from here to somewhere strange.

“… We got our lil farmlands, but you can see the erosion taking place.

“We will still remain until whenever,” he said.

As long as he is on the beach, Thornhill also wants to help monitor and protect the turtles that nest there. And he has been doing just that.

In mid-September, when most of the PAC rangers left the beach, Thornhill found a few hawksbill hatchlings on the beach. He instinctively collected them and kept them safe in his yellow bucket at his house until nightfall, the time when they could be left to venture into the ocean.

If he hadn’t picked them up, intense sunlight or dogs on the beach might’ve harmed them. Like Thornhill, Almond Beach residents all know the importance of protecting these endangered species.

Seeta Augustus, for example, grew up at the beach with her family. She relocated to attend a secondary school in Mabaruma, the capital town about 30 miles inland, but she’s now back as a ranger on the beach, helping to protect the turtles.

She can tell you many facts about the turtles coming to the beach. She also knows about the changes the community grappled with because of the erosion— the loss of the school, the church, and the ball field. The changes make her emotional.

“It’s very sad to know because it’s my hometown.

“…I born and grow up here, and now everything is washing away and it’s very hard to see, like, everybody moving away.”

“It’s really hurting,” Seeta said, trying to laugh away tears.

Coastal changes in Guyana

The Shell Beach area is part of Guyana’s low coastal plain, one of the country’s four natural regions, and the area that hugs the Atlantic Ocean. That coastal plain is particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels because it is itself below sea level.

At other parts of the coast, especially near more populated, urban areas, there are sea defences like mangroves and sea walls. These are necessary to help protect the coast and the people who live there.

Even so, the World Bank, in its 2021 report titled “360° Resilience: A Guide to Prepare the Caribbean for a New Generation of Shocks” found that Guyana could face the Caribbean’s second-highest level of shoreline retreat if high climate change impacts persist.

Essentially, it noted that Guyana risks losing 65 metres of its shoreline by 2050; only neighbouring Suriname (with an estimated retreat of 71 metres) risks losing more of its shoreline.

Local scientist and engineer Dr. Kofi Dalrymple has been studying the impact of climate change and sea level rise on coastal erosion for years.

According to him, the shoreline naturally evolves through a process of erosion and accretion but climate change is exacerbating that. In the case of Guyana’s coastal plain, much of the land was formerly marshland where the Atlantic Ocean would have naturally covered and receded over time.

With land development on the coast, however, he said the ocean has been kept “at bay” instead of allowing it to flow in and out naturally.

“What climate change does to that natural process is, as the sea rises, its ability to go further inland increases.

“So there is a direct link between rising sea levels and, sort of, coastline recession,” Dr. Dalrymple said.

Dr. Dalrymple said more research specific to the Shell Beach area would prove insightful. A study of wave intensity and coastline changes would help stakeholders grasp just how climate change is impacting the protected area.

Already though, the PAC, based on the information provided to the News Room, believes the erosion has “drastically” decreased the Almond Beach coastline and forced residents to migrate.

Still, the PAC believes that Almond Beach and wider, Shell Beach, still serve as a “viable ground for nesting sea turtles.”

Is inland migration a must?

The situation is a bit more complicated for those who still live there. Seeta’s father, Liston Augustus, retired recently after teaching for decades. He knows he should probably move more inland, but fishing and farming on the beach are his main sources of income.

“I have to try because I don’t really have any other alternative to where we can go.

“…When the water reach 10 metres, we normally break down our house and move away. This is the third time now we move away. It happens like every three years or so depending on how fast the water comes in,” Augustus told the News Room.

As long as the turtles continue nesting in the Shell Beach area, there will be efforts to monitor and protect them, but for the remaining residents who face losing their homes and livelihoods, inland migration may be their best bet.

Arnold Benjamin told the News Room that an area at Khan’s Hill, another Indigenous community found much closer to Mabaruma, is being prepared for the remaining families at Almond Beach. According to him, some may move, but some may remain on the beach.

This story was published by The News Room with the support of the Caribbean Climate Justice Journalism Fellowship, which is a joint venture between Climate Tracker and Open Society Foundations.