It is something we have taken for granted for years; turning on a tap anywhere, and out pours fresh water, so fresh that you can drink it straight from the tap, which we have grown accustomed to. What I have come to realise, however, is that even though we’ve had this blessing, it has been taken for granted. But now, reality has hit home: our freshwater supply is not immune to the vagaries of climate change and can be significantly impacted over a short period.

In St. Vincent and the Grenadines, high mountain ranges and dense forests ensure a water supply that is as pure as possible. The country’s lone water provider, the Central Water and Sewerage Authority(CWSA), has over the years managed to build a purely gravity-fed infrastructure, which means pumps are not required in its distribution process. The water comes directly from the source. It is treated and flows directly to homes and businesses through a complex, interconnected catchments and distribution systems network.

The recent dry period and the onset of a prolonged drought, which began in February 2024, were the tipping points in the abundant supply of fresh water. Though we have had ample warning from the Caribbean Climate Outlook Forum (CariCOF) since late 2023, no one anticipated the magnitude of what was about to happen. As February, March, and April elapsed and there was little to no rainfall, it became a matter of great concern not just for the farmers who depend on it but for the entire population, which requires a safe and continuous water supply. The data collected by CWSA shows a pattern developing that will soon manifest itself.

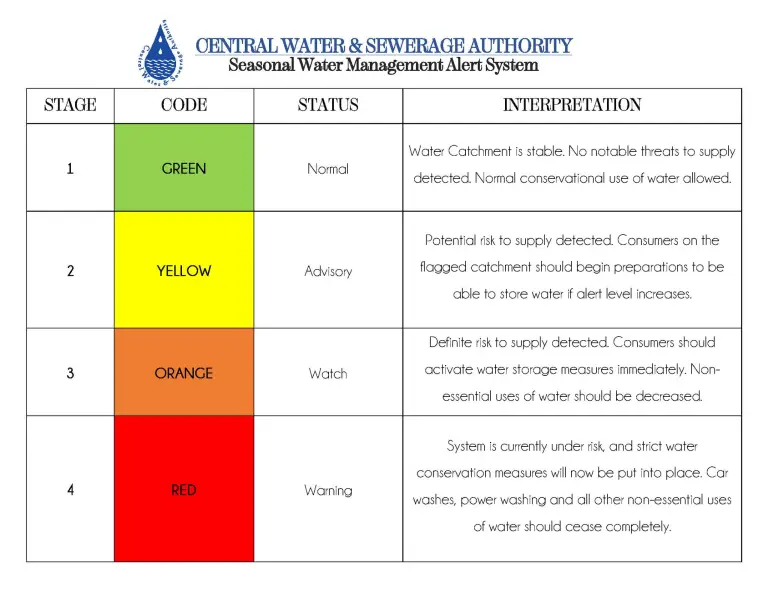

Though water rationing began in early April, the situation reached a crisis point around the middle of May, when the CWSA expressed concern about the dwindling supply and decided it was time to act. CWSA stepped up its public information campaign through the media and provided details of the status of the seven water catchment and distribution systems on the mainland. By the 15th of May, two major systems were now on red alert for deficient levels at the catchment system.

A press conference was hosted by the CWSA on May 14th and broadcast live on radio, television, and social media about the impending increase in water rationing measures. The continued worsening impact of the dry spells in the country had now resulted in the water supply rationing to communities supplied by the Dalaway, Montreal, and Majorca systems—the three largest catchments on mainland St. Vincent.

The CEO of the Authority, Winsbert Quow, described the situation as ‘phenomenal’ and pointed to the fact that climate change is the driving force behind more dry days and fewer wet days. He pointed out that the Dalaway system, which provided 40% of the island’s reserve, was dangerously low. This was attributed to less rainfall and increased temperatures throughout February, March, and April. It became clear that the rivers and streams feeding the catchment systems were at their lowest point in many years and, in some instances, reduced to a trickle.

In addressing how citizens can cope with the situation, the CEO urged investments in water storage systems, particularly for homes, and called for a change in attitude in the way Vincentians use water. He revealed that even through the driest periods with low water levels, there was no reduction in the consumption of water, which is a great cause for concern, and he urged Vincentians to desist from the unnecessary use of water during this time.

Petrona Cozier, who lives on the outskirts of the capital, Kingstown, was one of those affected by the water rationing measures. Like many affected by the rationing, she had to pay close attention to the rationing schedule to be able to store sufficient water for use in the household. Due to her location, when there was water, it was only a small stream, which sometimes limited her ability to handle matters that required the use of water.

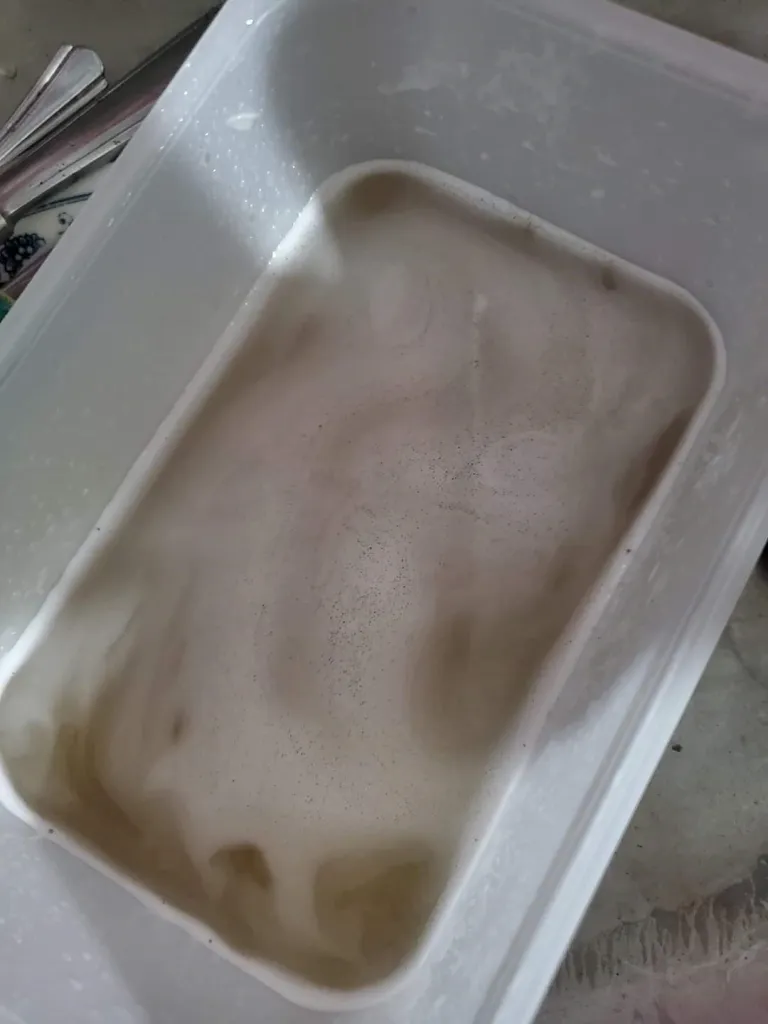

On some occasions, due to the extremely low levels at catchment sites, there was high turbidity, and the tap water came out with a foamy cocoa-like texture that was sometimes unusable in the kitchen or had to be left to settle.

The Grenadines was also affected, as the lack of rainfall and very warm temperatures had all but dried up the limited supplies stored on the islands. On many occasions, water had to be taken by ferry, trucked, and then distributed on the islands. This further added strain to the already limited supply on the island of St. Vincent.

Fortunately, some relief came a few days following the CWSA press conference, and the rains returned. Though it was not nearly enough to completely replenish the systems, it certainly improved the situation, if only temporarily. Later in May, the island again experienced some welcomed showers, which further improved the situation. As we progress into the official wet season, the expectation is that the water systems should return to normalcy in the weeks and months ahead based on forecasts.

Though very dry conditions were experienced during February, March and April, the latest precipitation outlook shows some hope of rainfall in the months of June and July, with a 45–50% chance of higher than normal rainfall. While the promise of more rainfall might seem like a good thing, too much rain can result in the opposite effect. More rain over a shorter period can result in landslides, flooding, and damage to homes and important infrastructure.

The question that remains is: what caused it to get so dire? Climate change is real. As we go from year to year, we see more temperature records being broken, droughts lasting far longer than they used to, and recently rising sea levels. It is unfair that though we, as small island states, contribute zero to carbon emissions and the depletion of the ozone layer, we suffer the most. The effects are felt by all, from farmers on land to fishermen at sea to the average man on the street. We must therefore take the bull by the horns and demand greater accountability from larger countries that turn a blind eye to smaller, poorer countries. The fact remains that though promises are made at COP summits by the larger emitters, very few stick to their word, and this must be a point for ongoing discussion globally to apply pressure for them to fulfil their promises.

—

This story was originally published by NBC St. Vincent and the Grenadines, with the support of the Caribbean Climate Justice Journalism Fellowship, which is a joint venture between Climate Tracker and the Open Society Foundations.