This year’s global climate talks, COP28, came to an end on Wednesday with countries agreeing to gradually stop using harmful fossil fuels, though some believe this agreement is not enough to help solve the climate crisis.

“We should be proud of our historic achievement and the United Arab Emirates, my country, is rightly proud of its role in helping you move this forward,” COP28 President Sultan Al Jaber said at the closing plenary at the Expo City, Dubai, venue.

The final deal is called the ‘UAE consensus’ and arguably, its most important focus is the call for countries (called Parties) to gradually use less fossil fuels to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

Those emissions include carbon dioxide, a harmful gas produced when fossil fuels like oil and diesel are burnt. When that gas is produced, it goes into the atmosphere and leads to global warming.

And countries were called to reduce their emissions in a number of ways including “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manager, accelerating action in this critical decade.”

Tripling renewable energy use (that is, using more environmentally-friendly energy sources like solar energy or hydropower) and other ways of using fossil fuels more efficiently were also actions countries were called on to pursue.

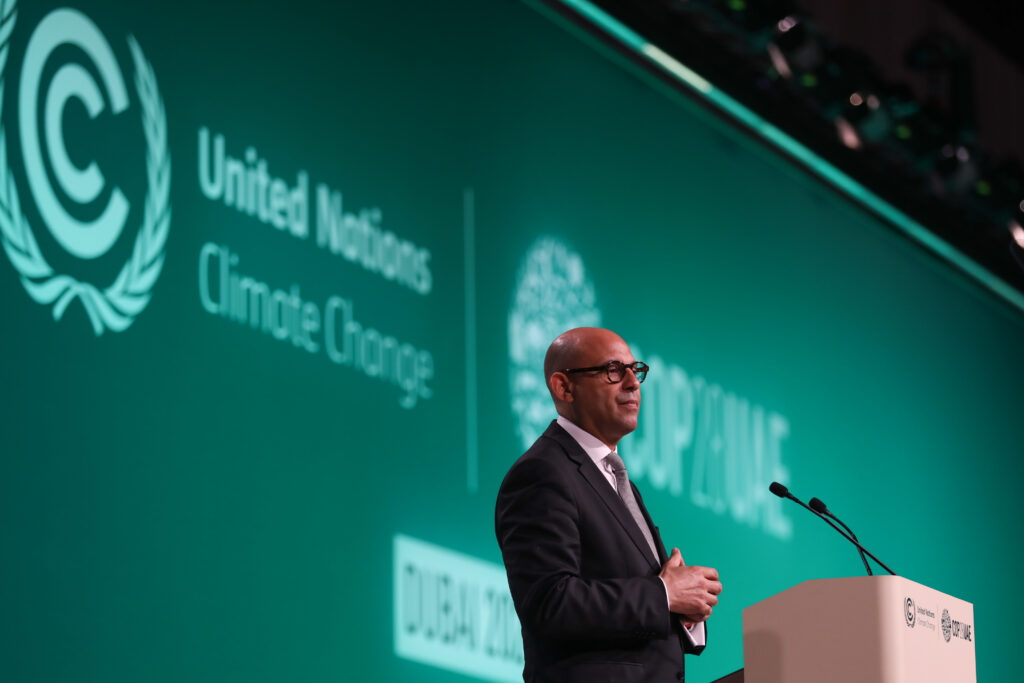

“… this outcome is the beginning of the end,” Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Simon Stiell said after Al Jaber spoke.

This is the first time a COP deal includes transitioning away from fossil fuels.

A focus on fossil fuels is important because as the Sixth Assessment Report of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) shows, about 90% of all harmful carbon dioxide emissions are derived from fossil fuel burning.

But not everyone sees the COP deal as a win.

Representatives of small, developing states argue that there isn’t a decisive focus on maintaining the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees celsius in reach. If that goal isn’t maintained, small, vulnerable countries will not fare well with some even threatened by disappearance due to rising sea-levels.

Samoa’s lead negotiator Anne Rasmussen, in the closing plenary, expressed dissatisfaction at the deal. She also said it seemed hurriedly adopted.

Samoa currently chairs the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), a grouping of 39 states including Guyana.

And AOSIS, in a statement, expanded on the reasons why the text is not sufficient for countries most at risk.

“… we must note the text does not speak specifically to fossil fuel phaseout and mitigation in a way that is in fact “the step change that is needed”. It is incremental and not transformational.

“… In paragraph 26 we do not see any commitment or even an invitation for Parties to peak emissions by 2025. We (see) reference to the science throughout the text but then we refrain from an agreement to take the relevant action in order to act in line with what the science says we have to do,” the AOSIS statement noted.

AOSIS has been among the groups pushing for a complete phase-out of fossil fuels instead of a phase-down or a transition away from fossil fuel use.

Secretary General of the United Nations, António Guterres acknowledged that the mention of fossil fuels, after years of having it blocked, is a step forward but emphasised that greater action is needed.

“To those who opposed a clear reference to a phase out of fossil fuels in the COP28 text, I want to say that a fossil fuel phase out is inevitable whether they like it or not. Let’s hope it doesn’t come too late,” Guterres said in a statement.

He added, “Of course, timelines, pathways and targets will differ for countries at different levels of development. But all efforts must be consistent with achieving global net zero by 2050 and preserving the 1.5 degree goal. And developing countries must be supported every step of the way.”

So what does this mean for Guyana? Much of what Guyana is doing, or plans to do, aligns with this deal.

For example, the country is forging ahead with the establishment of the Wales Gas-to-Energy plant that will be the natural gas produced in the giant Stabroek Block offshore used for cheaper fuel and in other production, like cooking gas.

Many persons, including Guyanese leaders, argue that natural gas is a good option to transition away from heavier or more environmentally-unfriendly fossil fuels like coal or diesel.

And since the countries have not agreed to phase-out fossil fuels, but gradually transition away from their use, Guyana’s plans to expand its nascent oil and gas industry can seemingly continue unaffected.

“We have made it very clear that we are going to develop the sector,” Guyana’s President, Dr. Irfaan Ali said during a Guyana side event during the first week of COP28 in Dubai.

According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) World Energy Outlook published in December 2023 report, it will have the largest global increase in oil production from 2022 to 2035.

The country is also mulling the use of new technologies, like Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), to reduce emissions from the sector. Already though, Guyana argues that its 18.5 million hectares of pristine forests trap way more emissions than the country produces or will produce at peak oil production.

Even at peak oil production (which is expected to be 1.6 million barrels of oil produced daily), the country’s Vice President Dr. Bharrat Jagdeo explained that carbon dioxide emissions would only be about 20% of the 154 million tonnes of carbon trapped by Guyana’s trees.

“We would still be nationally carbon negative,” Jagdeo said at the Guyana/ COP28 side event too.

In an interview with the News Room subsequently in Dubai, the Vice President highlighted that Guyana plans to get to net zero by 2050. Net zero, essentially, means cutting greenhouse emissions out completely, or as close to zero, as possible.

This story was originally published by the News Room, with the support of Climate Tracker’s COP28 Climate Justice Reporting Fellowship.