‘It’s really hot in here today, Miss,’ a student exclaims as the class teacher begins to prepare for her class at one of the secondary schools in Kingstown. The teacher agreed: It was a very hot Monday morning, with temperatures surely exceeding 30 degrees Celsius, way warmer than it usually is at 9 a.m. at the school perched on top of the hill. Though the classroom was equipped with a fan and was well-ventilated on both sides with louvre-type windows, this did not provide much relief. It was a still day with little to no breeze, even though the school was at the top of a hill that was usually breezy. The single commercial fan in the room circulated the already warm outdoor air and made matters worse in the confined space.

It was clear that the task ahead was going to be difficult, not only for the class teacher but also for the students. The discomfort on their faces was evident as sweaty students tried to keep themselves cool. It became clear that productivity would be at its lowest as most students were distracted by the heat or asked to be excused to have a drink of water nearby. This is just one classroom with this experience. What about the rest of the students? What about the teachers? How were they coping with this almost daily, especially over the last few months? The answers to these questions were very much the same throughout the school.

Official temperature datasets provided by the Meteorological Office of the Government of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines revealed that the daily temperatures between March and May 2024 were almost always above 30 degrees Celsius, with some days reaching as high as 32.5 degrees Celsius, which was unusually high for this time of year.

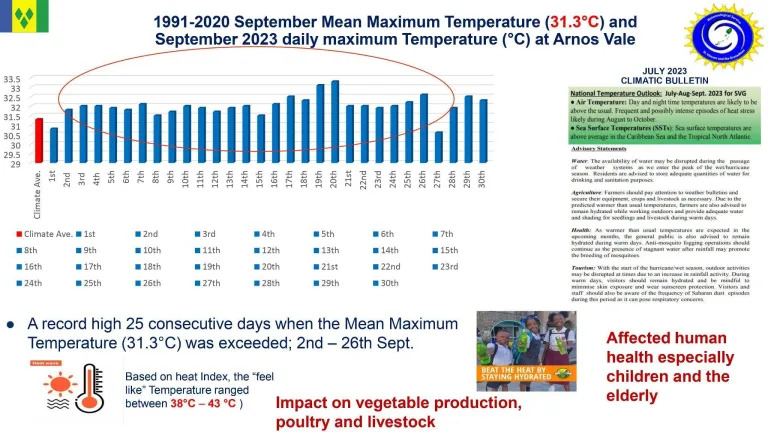

Combined with a surge in Saharan dust drying the upper atmosphere along with very weak trade winds, this was the recipe for hot and sticky conditions. This is by no means a recent issue, but combined with drought conditions and far less rainfall, it was even more evident that the real-feel temperature was higher than normal. Data acquired from the SVG Met Services show a very warm mean temperature of 31.3 degrees Celsius in September 2023 when the datasets from 1990 to 2020 were taken into consideration. Last September was also a record year, with 25 days of the mean temperature exceeding the 31-degree mark.

Now that you are aware of the data that shows the reason behind the warmer temperatures, let us return to the classroom setting. The last few weeks have been even more difficult for students, as it was the examination period, and students were confined to warm classrooms and had to remain quiet, and their movements restricted. In this particular classroom, for many reasons, the seating orientation was changed for the exam period. This not only allowed for easier monitoring of the examination process but also for students to benefit from the ventilation and fresh air coming through the louvres in front of them, and this seemed to work quite well, and students appeared to be more focused on the task at hand.

Mrs. Samuel, who is the class teacher for Form 3 at the Intermediate High School in Kingstown, said that even though the classrooms are well-ventilated and equipped with fans, it continues to be a challenge when the days are very hot, and she has observed that productivity is at an all-time low during this time as students are distracted trying to cool themselves and focus on class work at the same time.

Dr. C. Malcolm Grant, a local general practitioner and newspaper columnist, is one of those who’s been quite vocal about the effects of warmer temperatures on students and high-risk teachers. Dr. Grant attributes warmer classrooms to irritability among students and more disruptive behaviour. This results in frustration in many cases for teachers who are also trying to cope with the warmer-than-usual conditions. Dr. Grant recommends that, in addition to the proper ventilation of classrooms, other factors such as the configuration of the classroom, access to drinking water, awnings over sun-facing windows, and reflective paint be considered.

A possible solution, some may say, is the installation of air conditioning units to cool these classrooms. This, however, further compounds the issue when looked at broadly. Air conditioning units consume a lot of electricity. As over 90% of our power generation comes from the burning of diesel fuel, this is not only counterproductive to tackling climate change but also not feasible on a long-term basis.

In the overall scope of things, warming classrooms is something that we will have to deal with going forward as global temperatures continue to rise at an alarming rate. We continue to see the greater carbon emitters paying less attention to smaller and poorer nations. This puts us at a great disadvantage, as we are the ones most affected. The time is now for us to hold these countries accountable and call on them to do better at lessening their contribution to climate change.

—

This story was originally published by NBC SBG, with the support of the Caribbean Climate Justice Journalism Fellowship, which is a joint venture between Climate Tracker and the Open Society Foundations.